In June we had the opportunity to spend 10 days in Siena, a beautiful city full of traditions in Tuscany (Italy).

Looking for a place to stay, we found a small apartment inside a very old farmhouse in the hills outside of Siena. A community farming project was mentioned in the site description. We thought this looked interesting and so we booked it!

Not just a country house

Upon arrival, we entered the property through a small path lined with pointed cypresses (typical of Tuscany), olive trees and some fruit trees. At the top of the hill, we found a large, very old brick building.

We were greeted by Pietro, who, before taking us to the apartment, showed us the “oven room” on the ground floor. He informed us that Andrea comes three days a week in the morning to prepare bread for the cooperative and that if we see smoke we should not worry; the oven room becomes a bakery.

I love making bread, so I would not leave without meeting Andrea.

Before leaving, Pietro invited us to stop by the orchard that is at the base of the hill any day of our stay and, if we were interested, he would tell us about the project he is working on.

When we asked him for some vegetables to cook in the following days, he told us that the vegetables were collective and therefore to get them we would have to go to the cooperative store. How curious, right?

The next day, at the cooperative store, we bought vegetables from the orchard (delicious!) and in the evening we visited it (in Siena in June it gets dark after 9:30 p.m.).

The orchard is cultivated in an area of 1.5 hectares (107,639 square feet) and is home to 2 retired horses, one of which passed away during our stay (RIP).

Pietro lives on the property together with his partner, their young son, and some chickens and goats. The goats help to keep the grass down.

He told us that in addition to the orchard, the cooperative has planted fruit trees and that they have bees, the latter cared for by members of the cooperative.

The property is large and next to the orchard there are crops of wheat and olive trees (given in concession to third parties).

When we arrived, Pietro was leaving so we agreed to have dinner together another day. We would still have to wait to find out about the project and the famous cooperative.

A baker in the house

In the following days, we met Andrea the baker, a young man from around Siena who, seeing our interest in his bread, invited us to come at 5 in the morning the day after.

When I arrived, it was after 7 o’clock and Andrea was cutting the already leavened dough to prepare about thirty one-kilogram loaves for the members of the cooperative. He was very worried because the bread was not the right shape; it was a bit flattened.

To make bread you need: flour (various types of wheat or other cereals), water, yeast and salt. There are two types of yeast used to make bread:

• brewer’s yeast bought on the market is a monoculture of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and,

• sourdough yeast, which is a symbiotic culture of yeasts naturally present in the environment. Contrary to commercial yeast, the amount of sourdough necessary to prepare a certain amount of bread must be cultivated prior to its preparation.

The process of making bread is relatively simple. You mix the flour with the water, then add the sourdough and, at the end, the salt. The mixture is then kneaded for a certain time, left to leaven (or ferment)* for a set time at a certain temperature and at the end it is baked at the appropriate temperature and time.

*During the fermentation of the bread, the yeasts consume the gluten that is the protein of the flour and release carbon dioxide (CO2); yes, the same gas that we exhale during respiration. When we knead the bread dough, we create a gluten mesh that retains the CO2 that, trying to get out, causes the bread to inflate, or rise.

To obtain good quality bread, one needs to control the raw materials (flour, yeast, salt and water), temperature and time. Just a few variables, right? It cannot be that hard. In reality yes, mastering them requires the skills and knowledge of a specialized craftsman.

Andrea was very worried about the bread, so we made a “checklist” together.

Not just any bread

Andrea told me that the flour he uses comes from a farm that is growing cereals from an “evolutionary” population, meaning, made up of seeds of different varieties, mostly indigenous, that are sown and allowed to grow together.

The idea is that over time, the varieties that have best adapted to the climatic conditions of the soil in which they are found will prosper. Thus, the composition of the population that survives will be resistant to changes in climate and capable of sustaining high levels of productivity without the need for chemical products that are harmful to the soil.

The cooperative buys all the production of “resistant wheat,” which this year will be doubled. FYI, the evolutionary population of cereals is carried out together with the University of Siena.

Andrea used the same flour before the problem appeared, so the problem could not be the flour.

The knead is done manually by him, so it should not be it.

The laboratory where he works (the oven room) does not have an air conditioning system and the wood-fired oven is inside… additionally room temperature those days was high. It had to be the temperature that was influencing the growth of the yeasts.

Andrea was controlling the temperature all the time and reducing time of leaven to compensate for the higher temperature, but the bread was still flat…

Andrea is young and loves making bread. Surely with time, study and automating some variables, he will be able to obtain resilient bread even in the hot summer months. Yes, the bread was a bit fat but it was delicious!

Finally “the cooperative”

A few days before leaving, we met Piero who, during dinner, told us about his famous MondoMangione Cooperative Society, of which the orchard and the bread are part.

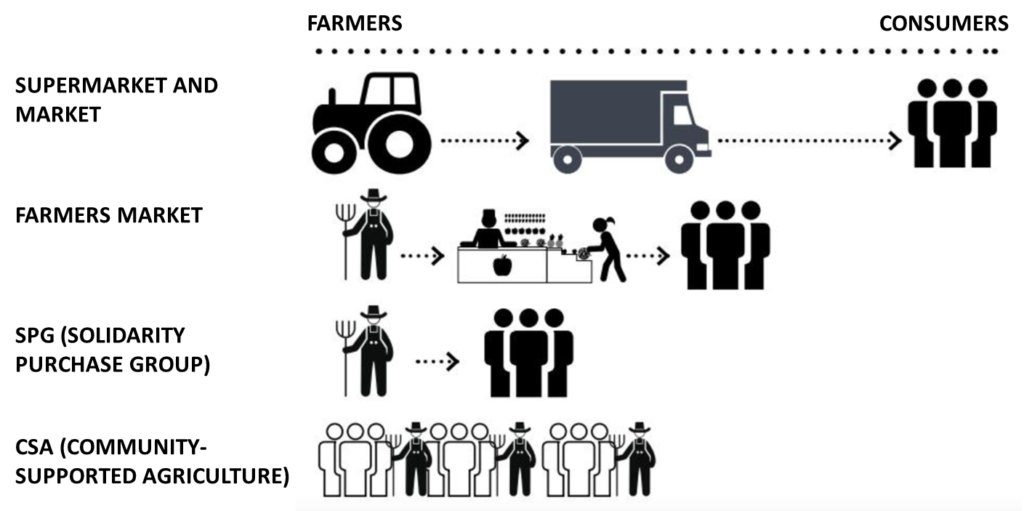

MondoMangione is a cooperative of conscious consumers that was born in Siena in 2004. It has created a small organized distribution of local, organic and fair trade products. The cooperative has the objective of establishing an economy based on the direct and transparent relationship between producer and consumer, respecting the territory, the environment and peoples work.

In 2019, they started with the OrtoMangione project, a collective orchard structured as a CSA (Community-Supported Agriculture) that has recovered 1.5 hectares of abandoned land. In 2021, the Il Pane dell’Orto (bread in the orchard) started as a collective baking project, also structured as a CSA.

CSA Model

The CSA model is practiced in Japan, United States, Canada, England, Italy, Germany, Austria and other places.

In Italy, there are three CSAs: Arvaia In Bologna (9 years of activity, almost 500 partners, 7 working partners, 47 hectares), Semele in Florence (70 partners) and OrtoMangione (the most recent).

In this type of agricultural cooperative, all resources (installation costs, equipment costs, labor costs, management costs) are provided by a group of people, who, in compensation, receive a part of what the orchard produces every week. They cultivate using natural methods.

The CSA model presupposes an active and participatory community.

Siena’s CSA

In the case of OrtoMangione, production is organized on the basis of business risk sharing, respect for food, waste reduction and support for worker members (Pietro and his colleague’s salary).

The “co-producer partners” (around 70 members) pay an initial fee of €75 as a contribution to the cost of setting up the orchard (75% as a donation and 25% as an association fee) and an annual fee of €750 (single payment or in 4 installments). They use the donations to finance necessary supplies, for example they plan to use the donations raised in 2021/2022 to fund a greenhouse and a new chicken house.

With the annual membership fee, partners receive a 5.5 kg box of vegetables (designed for a family of 2-3 people, with at least 5 varieties per week and 30 varieties of vegetables per year) for 45 of the 52 weeks of the year, and have the possibility of participating in the different activities of the orchard.

This cost may seem high, but for the economy of an average Italian family, considering that we are talking about healthy vegetables which are regenerating soil and generating jobs, it is an affordable price (€19 for a box a week). Costs have to be adapted to local realities.

As it is an active community, the partners commit to carry out at least one of the following activities:

• work in the garden (harvesting, planting, storage, maintenance of outdoor spaces, etc.) once a month for a minimum of 2 hours

• participation in the committee (1 meeting per month) or in working groups (administration, communication, events, etc.

• help with the distribution of vegetables on harvest days (minimum 2 hours per month).

What about the bread?

In a similar way for the bread, a group of people with an annual subscription pre-finance the preparation of a 1 Kg bread that they will receive once a week. In this way, the members guarantee the maintenance of an artisanal activity (Andrea’s salary) and the use of the wood oven.

The “co-baker partners” collaborate in the management and evolution of the project, and can participate in activities to share and learn how bread is made. Thus, the oven is open to all members, even to bake a mold of biscuits or a good cake using the oven that is still hot.

Projects like “the orchard” and “the orchard’s bread” give the opportunity to be part of a group of people who collectively care for a piece of land, create resilience and support tradition.

Pietro told me during the first year of production there was a fungal infection due to an error in the management of the greenhouse that compromised the entire tomato production. A lot of work and resources were at risk of being lost!

Due to the magnitude of the problem, the advised solution was to use a fungicide. The partners of the cooperative got together and decided that if the plants were sick, they had to be cured and thus they used the fungicide.

When tomatoes were ready, partners were informed about the previous fungicide treatment and people had the choice to take or refuse the tomatoes; some people refused the tomatoes.

By telling me this story, Pietro wanted to point out that we shall not blind ourselves on preconception.

Being part of a community can help us to stay open-minded, to understand the problems faced by our farmers and artisans and to be open to solutions to solve those issues.

Let’s create or be part of a community that stimulates exchange between people who live in the same place, producing essential goods, generating jobs, human relations and a redistribution system that eliminates waste and allows us to be informed!

Let us be part of a citizenship that actively creates the community in which we want to live!

By M. S. Gachet