Today I will tell you about a project I worked on last year: the design and maintenance of a small “nature-friendly garden” within the Vittore Buzzi Children’s Hospital in Milan.

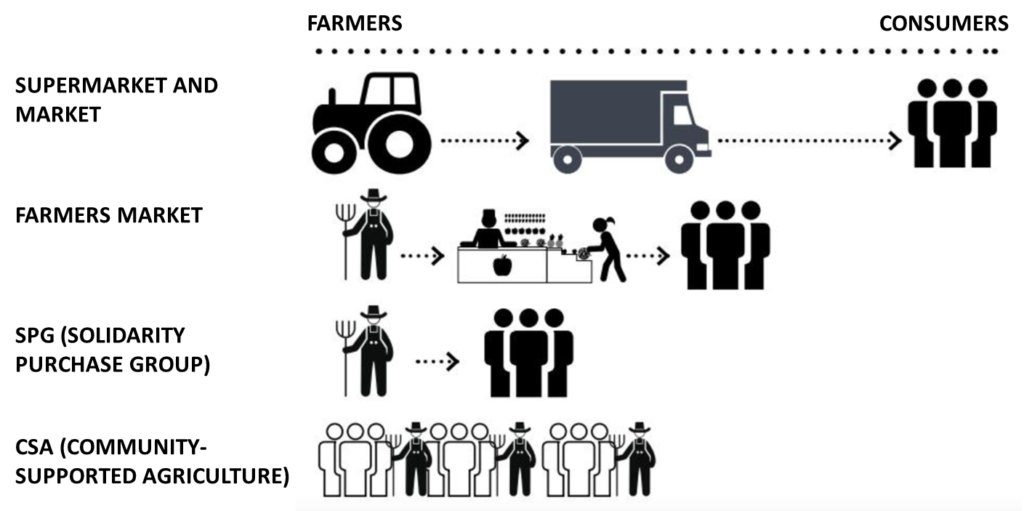

Since 2019, I have been an active member of a volunteer association that helped the municipality of Milan in planning and building a public park called Segantini (Associazione Parco Segantini (APS)). Now, its members (approximately 200 families contributing an annual fee of 25 or 50 euros) maintain three orchards, each measuring 1,000 square meters (m2), and a reforested area of about 15,000 m2 with over 1,000 native trees from the Po River basin.

It is a successful example of citizen participation that works not only because it has brought together people with different skills who share a passion for caring for urban nature and sustainable agriculture but also because genuine human relationships have been formed among its active members.

Thanks to this reputation, during the first months of 2022, the Missione Sogni (Mission Dreams) association sought help from APS to activate or reactivate gardens in some pediatric hospitals in Milan.

Missione Sogni financed the construction and maintenance of small gardens in pediatric hospitals for hospitalized children and their families. Additionally, they organized playful/educational activities once a week for those who could and wanted to participate.

After the COVID pandemic, it was challenging to re-establish collaboration with hospitals. Together with Antonella and Pamela from Missione Sogni, we visited three hospitals, of which only the Buzzi Hospital gave us the permission to use a terrace on the third floor to create a garden from scratch.

Cultivating in boxes is always a challenge because, unlike planting directly in the ground, plants, unable to reach underground water or nutrients, depend on our care to survive.

We formed a group of five APS members (Riccardo, Gabriela, Lino, Maurizio, and myself) to create the Children’s Garden at Buzzi Hospital:

- Water was made available to implement an automatic drip irrigation system and a sink, essential for working in the garden.

- Seven large and eight small robust plastic boxes were purchased and arranged in a “C” shape on the sunniest part of the terrace. Sunlight is crucial for plant life.

- Sacks made of a resistant plastic material were sewn to the dimensions of the boxes. They were placed inside the boxes and, on the top, a layer of volcanic stones was added to prevent water stagnation, followed by fertile soil.

- Two cabinets for educational materials and gardening, a small greenhouse, a rainwater collection system, a rotating composter, a sunshade, two tables, and several plastic stools were purchased and assembled.

With this, the essentials were ready to welcome plants, children and their families, and hospital staff. But what makes a garden respectful of nature? How does nature function?

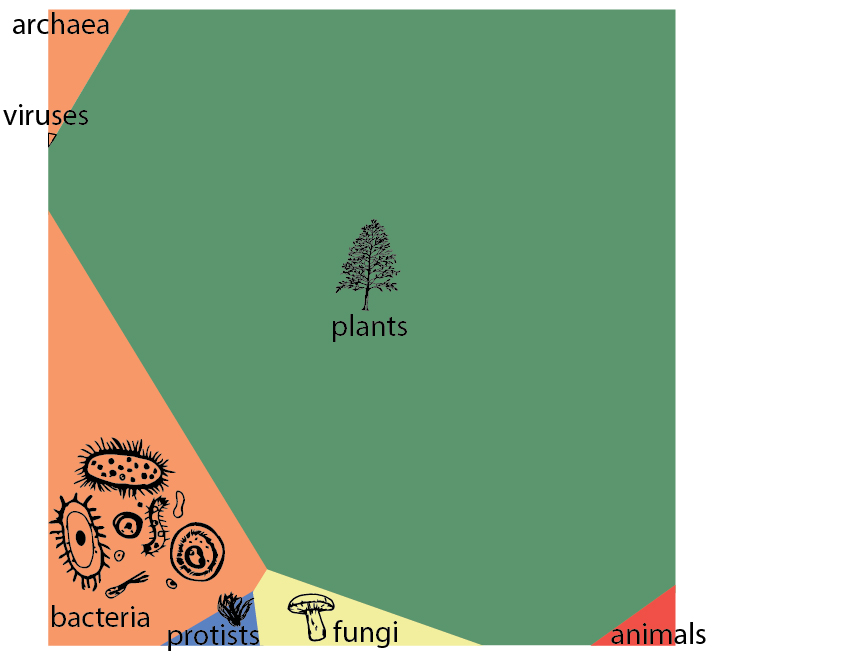

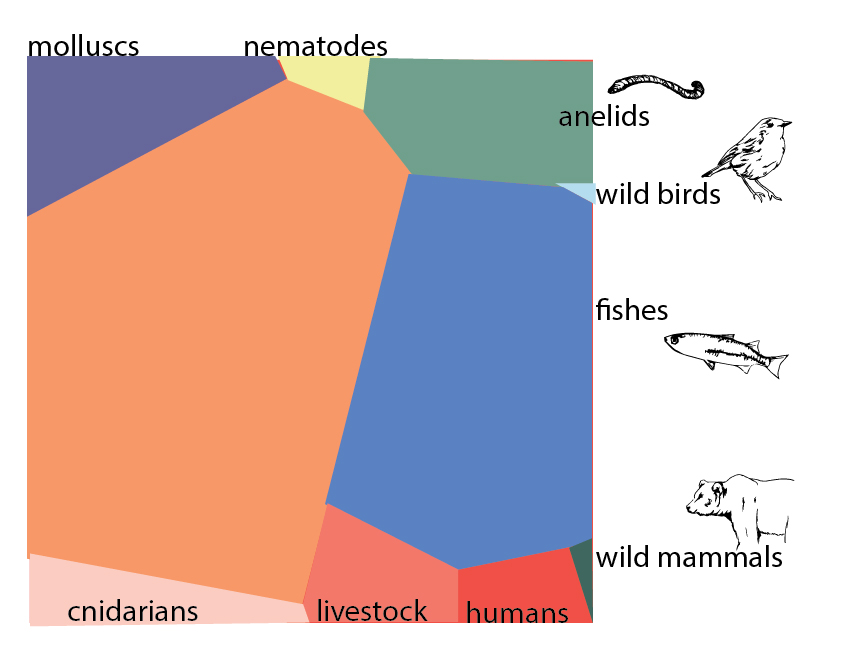

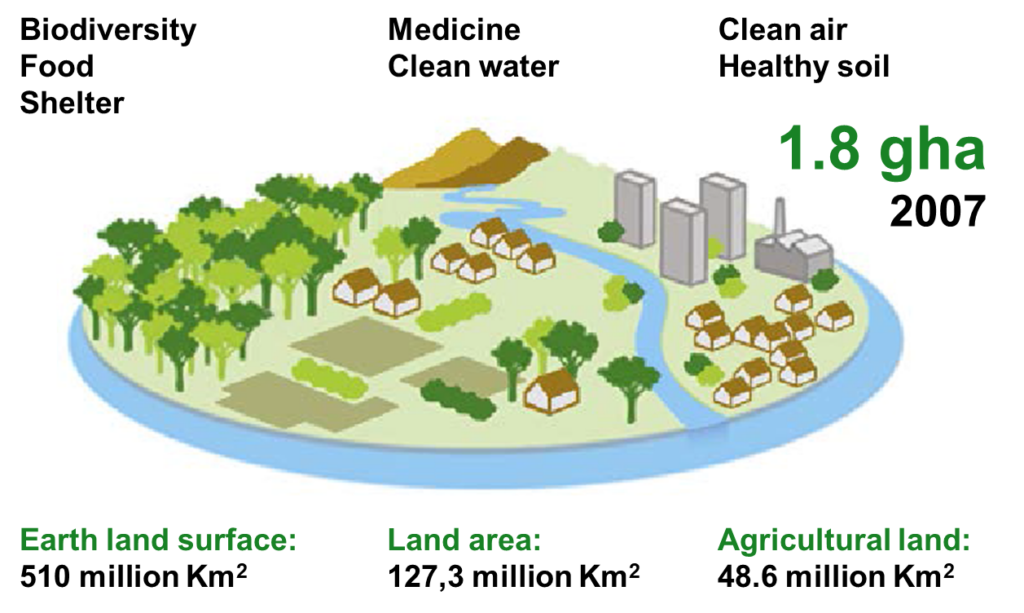

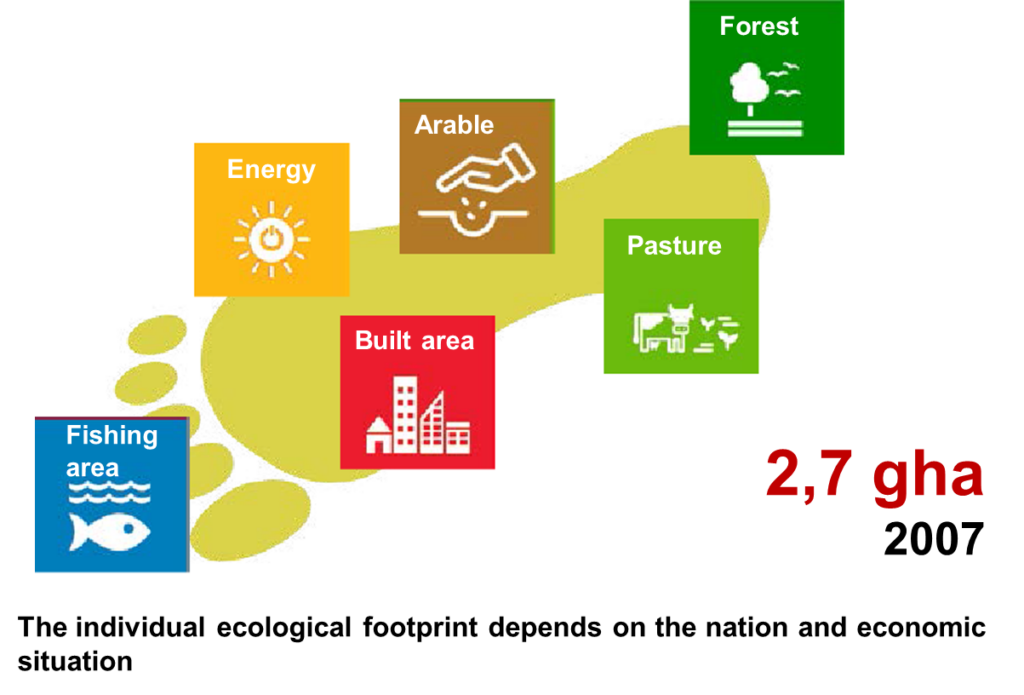

Let’s try to understand how a forest ecosystem works. Within a forest, many types of life coexist (plants, animals, fungi, and bacteria, and if there are rivers and lakes nearby, algae).

We needed to create a place where children and their families could observe, explore, and understand urban nature and its cycles, a place to produce some vegetables and fruits. A beautiful and lively place to rest and heal!

In the forest, the ground is always covered with leaves that fall from trees and, over time, transform into soil (organic matter) because microorganisms (bacteria, fungi) and macroorganisms (worms, insects) eat them.

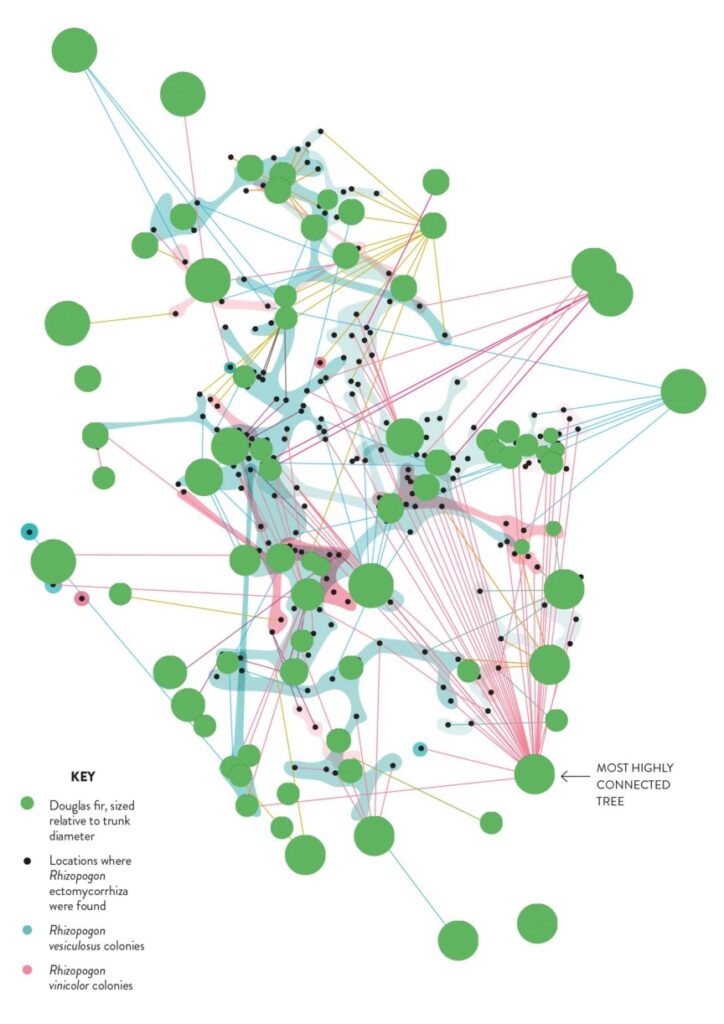

No one waters the vegetation in the forest because many interactions occur underground; for example, mycorrhizal fungi allow tree roots to reach water and minerals. A true system of exchange known as the internet of plants!

In boxes, on a terrace, on the third floor, plants cannot create these types of interactions. But if we integrate into the ecosystem as agents who care for and embrace life, agents who create beauty, they are able to live.

The first thing we needed was perennial trees and plants. So, we turned to Silvio, a key figure in the creation of the Segantini Park and one of the main contributors to the creation of Boscoincittà, a large 120-hectare forest in the northwest of Milan established since 1974 with the help of volunteer citizens.

Silvio knows many people, and thanks to him, three trees were donated for the children’s garden: ginkgo biloba, pomegranate, and red maple. We arranged them at the edges of the garden.

Considering that the garden was ready in June, the beginning of summer in Italy (and not the best time to start a garden), we bought some native plants found in the vivarium: three varieties of basil (Italian, red, and Greek), lavender, thyme, marigold flowers, lettuce, thornless blackberry, a blueberry bush, and another pomegranate.

APS gifted us calendula flowers, borage, a cherry tomato, and two peppers. And during the year they donated many other vegetables.

We transplanted the plants into the boxes, considering their space needs and the friendly conditions known to exist between them. Did you know that some plants love to be together while others cannot tolerate each other? The plant world is fantastic.

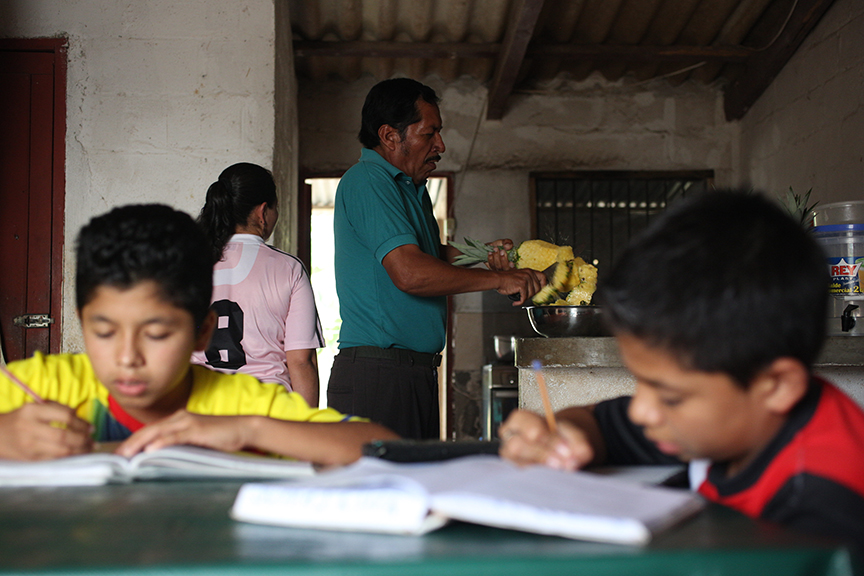

With the garden ready, (almost) every week (from June 2022 to September 2023), I dedicated two hours of work that included maintenance and an activity with the children.

Activities with the children had to be flexible and playful because they depended on the health and mood of the children and their families.

The activity was usually decided based on the garden’s conditions, the care it required, and the season (temperature, rain, and sun). Observation was crucial.

We used smell and sight to identify plants. We collected, identified and sowed seeds. Drew the plants. Harvested fruits from the ground. Stored rainwater for irrigation. Covered the ground with leaves and straw to protect micro and macroorganisms and prevent water evaporation. Prepared the ground for planting potatoes. Planted various flowers everywhere. Exchanged the unhappy raspberry for a madrone (a Mediterranean shrub-tree). Introduced more aromatic plants (sage, lemon verbena, rosemary). Made compost. Transplanted strawberries and learned their life cycle. Cultivated onions and carrots. Prepared pesto for the hospital staff, and so on.

Every week, Mery or a nurse from the ward informed me of how many children could come out if they felt like it. Luisa and Piera, the hospital teachers, also invited the children to participate in the activities.

Sometimes the children were very motivated and stayed for a long time, other times they were tired and decided to return to their rooms early, and sometimes doctors needed to visit them, and they had to return to their rooms.

I quickly discovered that even though the garden can allow for the experience to taste and discuss about nutrition, in a hospital context, this could not be proposed. So, the ripe products harvested were given to the hospital staff (doctors and nurses). Thus, the children cared for the garden plants (and the living beings that inhabit it) and gifted their fruits to the people who care for them.

Unfortunately, Missione Sogni, which financed maintenance and activities with children, ceased to exist in October 2023. Fortunately, another association present in the hospital decided to take care of the garden, so the plants will continue to bring comfort to children and their families.

The creation of this relationship of gratitude toward doctors and nurses through the delivery of products from the garden cared for by children and their families is the most beautiful thing I take from this experience. I hope it can be maintained and replicated in hospitals around the world.

Little space, respect, observation, and care are required to aid in healing and expressing gratitude for the work of those who heal us.

By M. S. Gachet