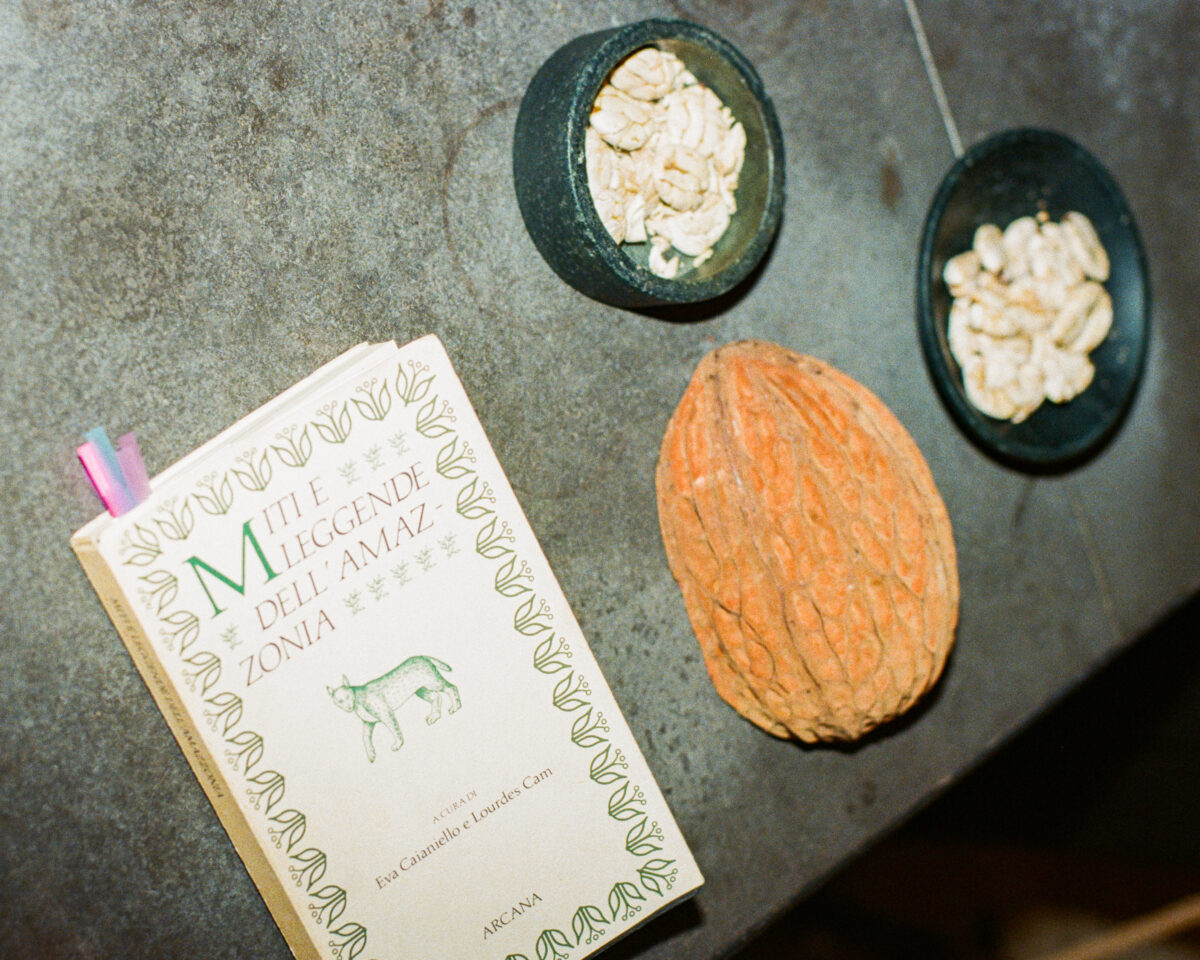

We told you in a previous post about the potential that Macambo seeds (a cousin of cacao) have to become a nutritious and delicious food that the Ecuadorian Amazon can share with the world (read the article Macambo as a solution. Chapter 1: The proposal).

We are not talking about just any superfood, but about one that supports the economic activity of a group of indigenous farmers of the Kichwa nationality who cultivate in a respectful way (within ancestral agroforestry systems) for their own consumption (and for sale) while conserving the local ecosystems and thus protecting the Amazon.

This type of agriculture can represent an alternative to mining, intensive agriculture or logging.

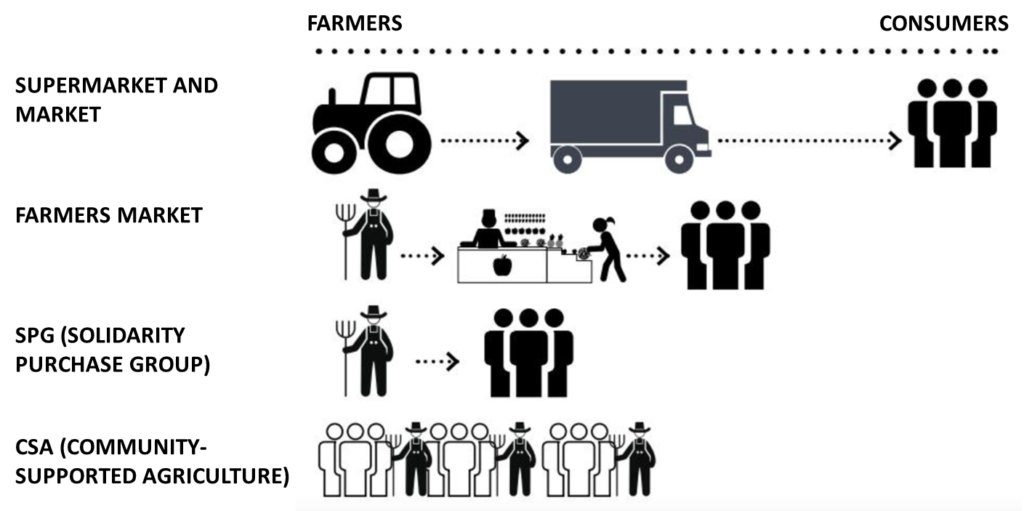

We also told you that we are trying to connect these producers with a group of consumers who support the annual purchase of 200 Kg of dry macambo seeds that justify the import by sea from Ecuador to Italy once a year after the harvest. We thought that perhaps chefs attentive to these arguments might be interested in embracing and valuing macambo, a rich and nutritious product with identity and positive social and environmental impact.

This proposal began to take shape after my meeting with Sara Nicolosi and Cinzia De Lauri, two chefs from the vegetarian bistró AlTatto in Milan. Their cooking philosophy highlights vegetables, quality, seasonality and where food comes from. They loved the idea of valuing a product belonging to the culture of the Kichwa indigenous people of the Amazon region of Ecuador. They gave me the contact of some colleagues who they thought might be interested in creating a community, to discover and make this Amazonian seed and its history known to the people of Milan.

After some meetings, calls and a little time, on Monday, October 2, AlTatto opened its doors to welcome the culture behind Macambo. The cooking philosophies of 6 chefs, Simon Press (Contraste), Denis Lovatel (Denis pizza de montaña), Francesco Costanzo (Pasta Madre), Aurora Zancanaro (micro panificio Le Polveri), Mutty and Sara and Cinzia (AlTatto), praised this distant guest.

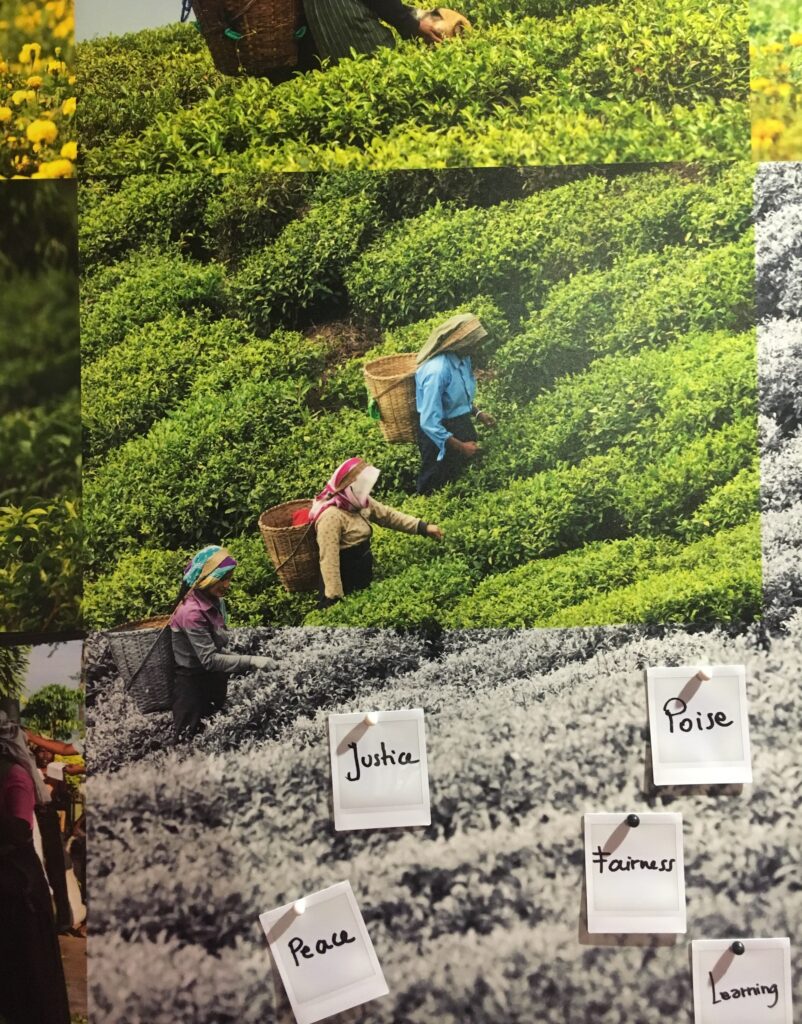

The event began with a short introduction of the project followed by a reinterpretation of “chucula”, a delicious drink made with ripe plantain served with ice. Meanwhile, people asked questions, read about the project and saw the photos that told this and other stories of indigenous communities from the Ecuadorian Amazon and their fight to conserve this magical place full of life.

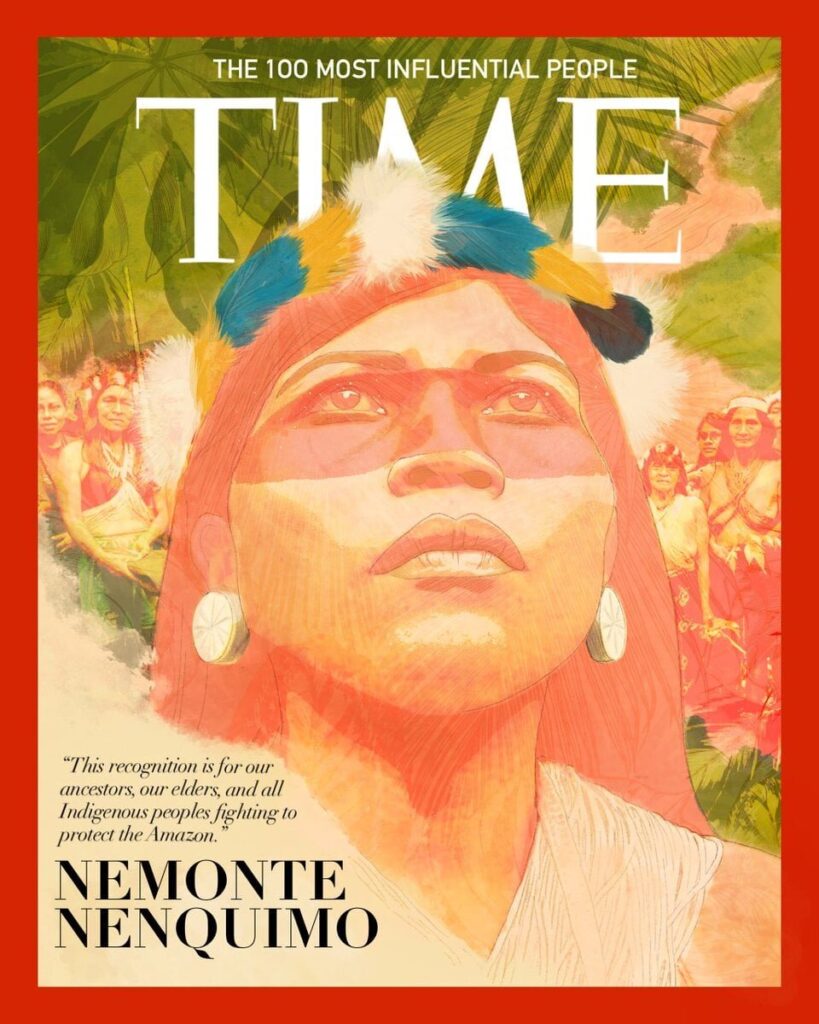

The story of Nemonte Menquino, indigenous leader of the Waorani nationality, tells how together with her people, they defend their ancestral territory, culture and way of living. The story goes on to talk about how in 2019, they obtained a historic victory against the Ecuadorian government to protect half a million acres of primary Amazon rainforest from oil exploitation, setting a precedent for the rights of indigenous people throughout the region (more information).

Another story was the long fight to protect the Yasuní National Park, one of the places with the greatest biodiversity on the planet and home to various indigenous communities, including groups that live in voluntary isolation, Tagaeri and Taromenane. In 2007, the Yasuní ITT initiative proposed to the governments of several rich (polluting) countries to grant compensation of 360 billion dollars over 10 years for leaving Yasuní oil underground (half of the expected profit from sales). The proposal did not materialize and oil exploitation began in 2013. After 10 years, in the referendum of July 23, 2023, the citizens of Ecuador decided to suspend oil extraction in the Yasuní within a period of 1 year, a unique precedent in the world (more information).

Little by little, small tastings with the chefs’ creations arrived in the room: Sara and Cinzia decided to respect the purity of the macambo seed in its essence, consistency and aesthetics. They toasted it lightly and added two flavor enhancers: caramel flavored with fig leaves and salt. Delicate and delicious!

Francesco proposed a macambo crumble with goat cheese and fresh seasonal figs. The crumble was made using the Sicilian tradition (Francesco’s region of origin) which normally uses almonds. He hydrated the macambo and then made a cream with it. Latter he added only rice flour and oats to prepare the crumble, no animal fat! Sicily embraces and welcomes macambo, a delight!

Aurora prepared a delicious puff pastry with salted macambo frangipane. Frangipane is a cream made from almond flour. Aurora uses flours that come from small artisanal mills in Italy and she seeks to rescue old cereals abandoned over time to rediscover lost tastes… and discover new ones with the same attention.

Simón explores a lot with the memory of taste in his cuisine. But aware that macambo taste is unknown to both him and the Italian public, he decided to play with geographically familiar flavors. Thus he used black corn, guajillo chili, passion fruit and cocoa beans in its creation. To create a flavor contrast, he added a product of Italian tradition, mullet roe. Very good and interesting!

Mutty made a Mediterranean-style macambo canapé by blending the macambo seeds with eggplant, tomatoes and basil. On top of this she placed a bean cream and fermented lemon, this last one to create a contrast of flavors. Finally, it was sprinkled with dried blueberries (mirtilli) and mint powder. A delicious Mediterranean welcome for macambo!

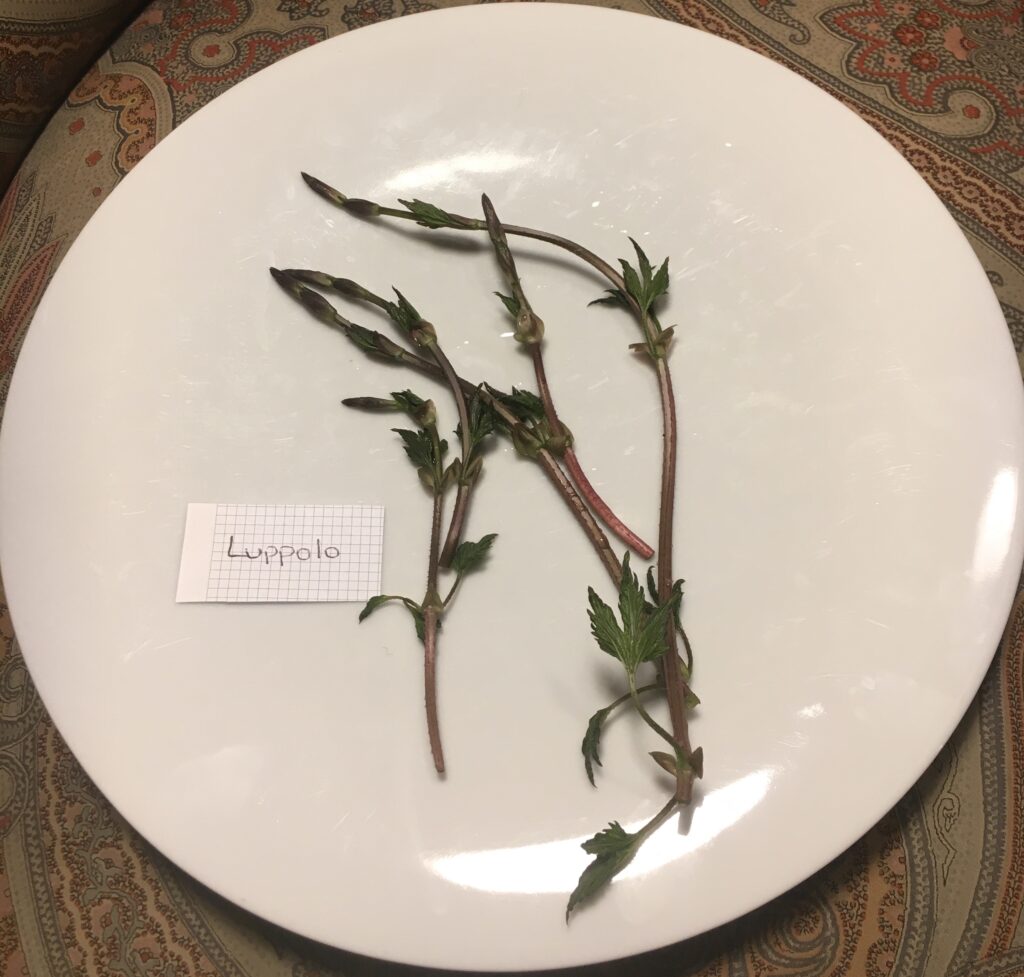

Denis proposed a semi-integral pizza-focaccia with “fior di latte” (a kind of mozzarella), mountain herbs, chutney with berries (forest fruits), granulated toasted macambo, misticanza (meadow) salad and a green apple vinaigrette to cleanse the mouth in the end. This pizza is a journey through mountain flavors. The crunchiness and final taste are given by the macambo.

His idea was not only to play with consistencies and flavors but to unite two distant communities with similar philosophies of life: the forest of the Italian alpine mountain of Bergamo and the Amazon rainforest. Both are small communities, circumscribed (isolated) within a specific ecosystem, with lifestyles and rhythms different from those of the city. They are both places where food is grown for self-subsistence, where food is harvested respecting nature rhythms, where food conservation methods are important to survive and where resources are used efficiently (avoiding waste).

In the end, Rosa Linda Yangora Pichama, a Shuar indigenous woman (another indigenous nationality from the Ecuadorian Amazon), told us a little about her culture and what the rainforest means to the Shuar people, reminding us how important it is to conserve cultures that live in harmony and respect with nature.

We have not yet met the 200 Kg demand target that guarantees the efforts to import macambo this year. Our deadline to make the first import is October 27, 2023. If this happens, macambo will leave Ecuador in November and will arrive in Italy after 6-7 weeks. If you are a chef in Italy and are interested in purchasing at least 10 Kg of macambo, please contact us ([email protected])!

The transport of small volumes (<300 kg) by sea appears to be uncommon. If we manage to activate the import we will tell you what the process is like to import Macambo in Italy. Stay tuned!

By M. S. Gachet